I started talking about this razor elsewhere and decided to finish it up here on my own blog. Here I don’t have to tolerate the occasional piss ants who attempt to garner attention for themselves arguing about truly idiotic ideas based on their own limited skills and knowledge base on the premise that there is no right or wrong about building razors… a premise, mind you, that there are only opinions and no facts. Sheesh! The trouble with ignorance is that it picks up confidence as it rolls along. More on “Razor Balance” later, right along with where I point out the difference between an opinion and a fact. I digress… back to the damascus razor.

In an effort to get all controversy out of the way from the get-go, I would like to mention that my use of the term “damascus” can raise the hair on the back of the neck of some boys. Lately, it seems to be a bone of contention with many guys in regards to the true meaning of the word as it relates to their entire bank of knowledge... Wikipedia.

Some insist that “pattern welded” steel is not the same thing as damascus steel. Fine. I’m not here to argue any of that. Call it what you want. For the purpose of this blog entry, however, I’m referring to the razor being made as a damascus razor. I called the maker of the billet, Robert Eggerling, and asked him if he calls his steel damascus or pattern welded. He said that either is fine, but he refers to it as damascus. That’s good enough for me. His word trumps all the dinkweeds who probably just spent most of the week running their fingers through the toilet paper.

I have made razors in the past using damascus with varied results… with most of them not meeting my standards or expectations. When the same steel is used on a knife, I have achieved killer results. The problem with making razors has been that, invariably, two or more of the steels in the damascus wind up meeting in several places along the cutting edge at some pretty steep angles. Because the edge is very thin, the damascus, regardless of who made it, had a tendency to microchip at those junctures. The razor would function, but it was not a comfortable shave. They were also a bear to hone and strop. A good size chip in the edge would also mar a good strop… that’s not good either. Aside from a Zowada razor, I think you’ll find that most folk were not all that thrilled with anyone else’s damascus razors, including mine.

I have found that this microchip anomaly is characteristic of most damascus or pattern welded steel made in the past 10 years. This was the primary reason I quit using damascus for razors for many years. It surely was pretty… it just didn’t function very well. I haven’t tried powdered damascus, so I cannot comment on any advantages or disadvantages on those. Sandwiched steel doesn’t even count in this discussion. It’s great stuff, but it’s unrelated.

An excellent knife/razor maker, Tim Zowada, solved the microchip problem by running the pattern parallel to the edge. I decided to tackle the problem a little differently. I had Robert weld a narrow strip of 1084 carbon steel on the edge of the billet. That way I get the beauty of the damascus and the surefire edge of a solid piece of steel along the cutting edge. You get the best of both worlds, so to speak. I only refer to “beauty” in damascus as the forefront of desirability because modern steels are as good if not better than any damascus around… past or present. So, I’m saying it’s my take that damascus is mostly for looks rather than function in this day and age.

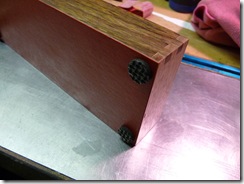

The very next step in production after the steel comes through the doors of my workshop is to profile the shape of the blade. I decided to use my original humpback design and dress it up a bit later on down the road. Here is the preliminary outline/profile with the Burr King grinder and specific attachment I used to do that portion of the work.

Once the profile is ground, what is called the “master grind” is applied to the blade, giving it the 1/4 hollow ground shape along the cutting edge. All my razors are 1/4 hollow ground. The thickness at the cutting edge is kept above .030 of an inch for now. It’s also a bit rough… like an 80 grit finish. Before heat treating the blade, I will take it down to .025 of an inch and use a 120 grit belt. I cannot go thinner at the edge because the 1,500 degrees necessary to heat treat the blade would warp the entire cutting edge, making it look like the bottom fin of an electric eel.

At this stage, some detail is added. The hole for the pivot is drilled and the tang is tapered to take a bit of the weight from the back of the blade. Since I decided to gussy this one up a bit, I had to practice my engraving skills a mite to include some wire inlay. I used copper and brass for practice, but knew that I would be using pure 24K gold wire inlay for the final design.

Using gold wire is not for the faint of heart. Especially at today’s prices for gold. I’m going to use 24K, 24GA wire. As you can see, it’s not cheap. I’ll probably use half of what is in the package.

Here is the gadget I engrave with. It’s a contraption that acts like a miniature jackhammer with the power coming from a machine that delivers air to the handset with variable beats per minute. The range is from about 400 to 8,000. Most work for me is in the 2,200 BPM range. Gold is pounded into the channels at 1,400 BPM. The chisel-like tool in the end is called a graver. They have to be precisely sharpened with special fixtures on diamond hones to achieve optimum performance. The gravers come in different shapes to do different tasks. If you want to learn how to engrave, there is a dandy place in “tornado” Kansas to learn. It’s called GRS tools. All the info is on their site. Ask for Linda. Tell her I sent ya.

For wire inlay, I put in a square “trench” with a flat-edged graver. After the depth is slightly more than half the diameter of the wire, I go back and undercut the entire length of the trench at the outer edges on both sides so that the gold does not come out after it is pounded in place.

The next pic shows some copper wire that has just been pounded in place in one of the designs I considered using for the tang on the razor. I got to thinkin’ it may be too busy and went with something else. Stay tuned. The second pic shows what it looks like through the stereoscope I also use to do my engraving. You will see where I have started to cut the excess wire flush to the surface.

Here are the next progressions in pics. The first show the tip configurations for the gravers I use in the magnum hand piece. The second shows the wire cut flush and sanded. Now, the wire has to be outlined with what is called a “square” graver. It is tilted on edge to form a “V”. I also change the degree of the angle of the “V” on the graver to 105 from the standard 90 degree angle.

I’m going to give it a rest with this section. I’ll come back shortly for part two, etc…